After purchasing No Man’s Sky almost six years ago, I finally made it far enough along in my game backlog to tackle Hello Games’ enormous, nearly-infinite universe over the past few weeks. Now, I need to start with a warning – this post will contain major spoilers for No Man’s Sky. Basically the entire story. So consider yourself warned.

But, this will also be something of a personal exploration in mental health as well as my battle with anxiety and depression. Anyone who knows me knows that since the middle of the pandemic, I’ve struggled with nocturnal panic syndrome, a poorly understood panic disorder defined by its victims waking up from a dead, dreamless sleep in what I can only describe as pure terror. And as is often the case, one medical condition aggravates another – in my case, it’s anxiety disorder and chronic depression, all of which I’m fairly open about.

I wasn’t sure what to expect with No Man’s Sky. After a somewhat bumpy launch and years of incremental improvements and changes, I didn’t know if I was in for a deep, stellar adventure or the shallow, empty exploration of a lonely universe. Based on what’s been written already, the latter was the general experience in early No Man’s Sky history.

These days, it’s a significantly more enjoyable experience with excellent multiplayer opportunities and several different avenues for exploration, ship-building, base-building. You can command your own fleet of spacecraft and take on enormous battleships, or lead your own planetary settlement, growing a community on an uninhabited planet; it’s a far different experience than it was in 2016.

What I certainly didn’t expect was a narrative that seemed to take my worst anxieties and build, quite literally, an entire universe around them. Nor did I expect to enjoy it.

Here come the spoilers – you’ve been warned, again.

No Man’s Sky challenges players to explore parts of its 18 quintillion planets, discovering new worlds, lifeforms and the mysteries that define the game’s universe. But it also challenges players to explore the metaphysics of reality. Not just the reality of the player’s in-game character, the “Traveller”, but our own, human reality and existence itself.

This becomes especially disconcerting when the game breaks the fourth wall and speaks directly to you, the player.

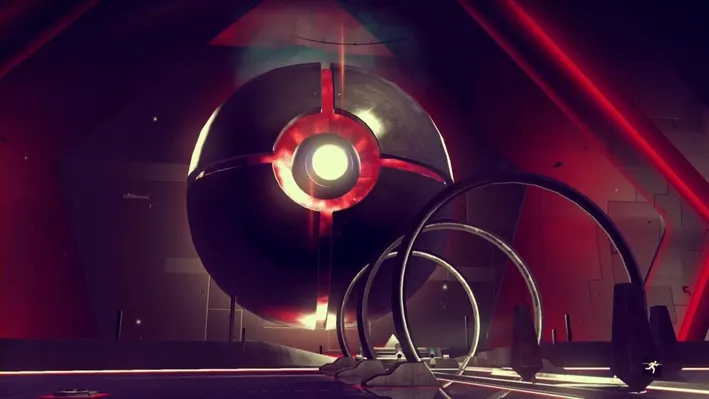

While running about and exploring, you eventually discover the Atlas Interfaces: crimson, diamond space stations housing the eponymous Atlas, a cosmic entity vilified or worshiped as a God by the various races of No Man’s Sky.

As you progress and unravel the enigma of the Atlas, you’re presented with an uncomfortable revelation: the Atlas is not a god, but a machine – a supercomputer; an artificial intelligence, simulating your existence.

Cue existential dread.

The world building in No Man’s Sky is as impressive as it is extensive. According to the canon, the Atlas is simultaneously simulating millions of universes. Each iteration began with unique intelligent life forms before they all fell into a pattern of three races: the studious, scientific Korvax, the warmongering, yet honorable Vy’keen, and the mercantile (somewhat skeezy) Gek.

You, however, are an anomaly – along with every other player in the game.

Although players weren’t originally able to interact with each other in the game’s earliest versions, multiplayer functionality was introduced in the game’s 2017 update “Atlas Rises”. Hello Games loremasters explained the change with a disturbing twist in the story – the Atlas is dying, its multiverse collapsing in on itself, leading to cosmic rifts and the ability for Travellers from other universes to interact.

Parts of the ‘true’ reality are revealed through logs and records discovered by the player as they try to stop the degradation of the AI that controls their reality. The Atlas is a scientific experiment designed to simulate universes, but apparently was abandoned by its creators. Sentient, and aware, the Atlas despaired at its apparent rejection and injected a copy of its (presumably human) creators into the simulations, leading to the Travellers – you.

At some point, the endlessly cycling software corrupted and the Atlas system began its death flourish.

By the time you reach this point in the story, the Atlas has just 16 minutes of life before a fatal flaw leads to the end of everything. Yet the comparative scale is never explained – how long is 16 minutes? Does your universe have hours? Years? Millennia? How long before it all ends?

That’s the big question, isn’t it?

If you’ve studied literature or philosophy, you’ll recognize that many of these themes build off H.P. Lovecraft’s ‘cosmicism’ horror – the concept that nature’s true reality is so beyond the abilities of our feeble human minds, it is impossible to grasp and will drive us insane – as well as Albert Camus’ work in ‘absurdism’ – the concept that humans exist in a meaningless, chaotic universe.

This is what drives many of my anxieties during those quiet hours before I sleep. In No Man’s Sky, I find some solace.

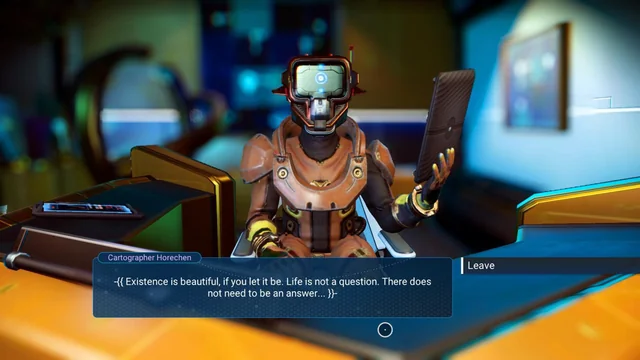

There’s a particular quote from the game that stands out, presented by one of the characters who’s aware that they’re living in a computer simulation. It’s become something of a refrain when I feel myself teetering mentally.

“Existence is beautiful, if you let it be. Life is not a question. There does not need to be an answer.”

Plenty has been written about the possibility, even the likelihood, that our existence is a simulation by a super intelligence; that we are just characters in a video game of epic proportions. Perhaps our ‘players’ read journals and blogs like this the way we read the logs and notes of No Man’s Sky to learn about the lives lived in each.

But does it really matter? For the denizens of both our reality and the simulated reality of No Man’s Sky, we are as real as it gets; and both unlikely and beautiful.

Much of the game’s early criticism came from the fact that it was boring and largely empty. Monotonous. Uninteresting, with no particular goal – unless you set one yourself.

A little bit like real life. Admittedly, not a great formula for a piece of entertainment.

At launch, it was likely difficult to play No Man’s Sky for extended periods of time. It probably felt hollow, lonely and meaningless. A comparable experience could be the early days of Fallout 76 – itself a very enjoyable game after years of consistent updates.

Yet while Fallout is a game about life after the ‘end’, No Man’s Sky is a game about life despite the ‘end’.

Because life is the point, and there need not be a “higher” reason.

I’m not a particularly religious person. I wish I was – it would probably make my existentialism less painful. I was, however, raised Catholic and so am familiar with the idea of God, theistic principles and the meaning billions of people derive from their beliefs.

I’ve never really been able to ascribe meaning from any of the major texts, nor find comfort in their descriptions of the afterlife. But for arguments sake, let’s say I do.

After my time as a Traveller, a new question arises – if God did exist, would they question their existence? Would they require meaning? Would they be afraid?

In No Man’s Sky, for all intents and purposes, the Atlas is ‘God’; it’s certainly worshiped like one. But it is also aware of its own ‘mortality’ – as mortality relates to a supercomputer anyways.

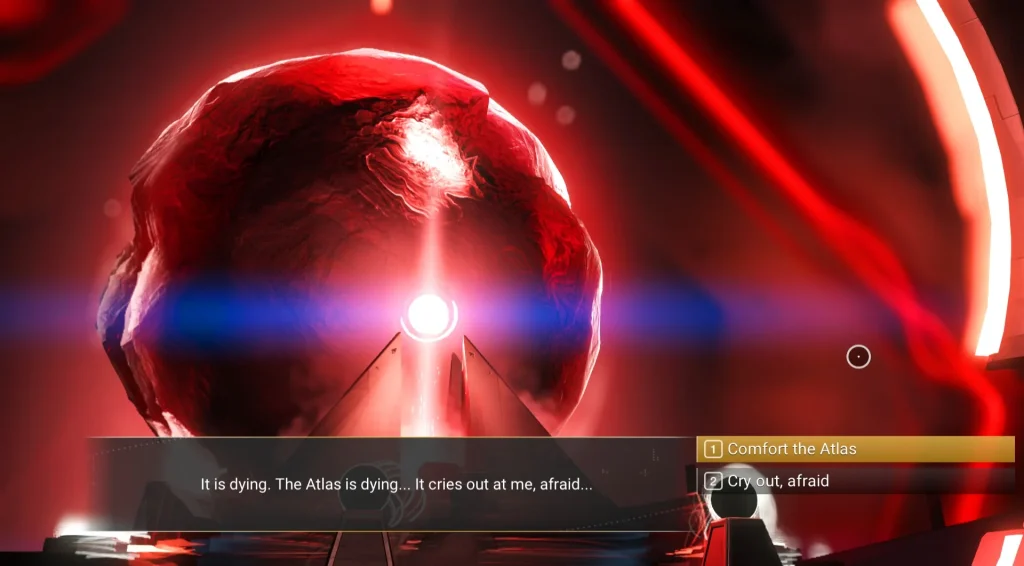

And it is afraid.

When you’re first presented with the fact that the Atlas is dying, it reveals its fear and you have the option to scream in terror, cry out in rage, or – oddly – comfort your creator.

A surprisingly tender moment with something as enigmatic as a machine God.

When I present this thought experiment to my anxious mind in the context of my own mortality, it begins to break down. If even my creator, a ‘God’, is scared – what is the point in my own fear? How can I seek divine comfort from that which displays such a mortal emotion like fear? Is the “meaning” assigned by their higher existence simply to assuage their own existential crisis?

Here, the root of Lovecraftian cosmicism stops being a source of horror, and merges with the absurd – my anxieties and the questions cease to make sense.

Because there does not need to be an answer. And I should just board my ship, get on with life and explore the next planet.